Hepatitis B is an inflammatory illness affecting the liver. It is caused by the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and is an infectious condition. Roughly one third of the world’s population has been infected with Hepatitis B at some point of their lives, while an estimated 350 million people are chronic carriers.

The acute form of this illness can cause liver inflammation, jaundice, vomiting and, in rare cases, even death. The chronic form of Hepatitis B, meanwhile, can eventually lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer. Vaccination, however, can prevent infection.

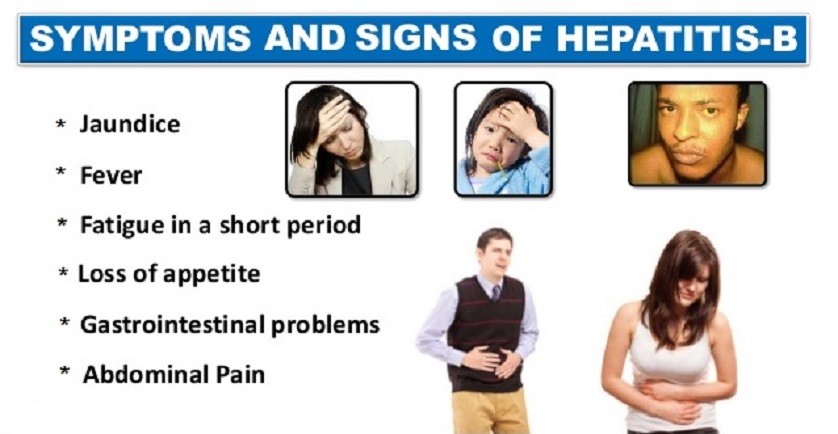

Signs and Symptoms of Hepatitis B

The acute infection with the Hepatitis B virus is typically tied to acute viral hepatitis. This illness kicks off with general ill-health symptoms, loss of appetite, dark urine, vomiting, mild fever, body aches, until it progresses to jaundice. Itchy skin may also be a potential symptom of all types of the hepatitis virus.

In most patients, the illness persists for a few weeks, after which it gradually ameliorates. In rare cases, patients may experience more severe liver disease fulminating with hepatic failure, which may result in death. The infection can also lack symptoms altogether, passing unrecognized for years on end.

Chronic Hepatitis B may be either asymptomatic or associated with a chronic inflammation of the liver. In a few years, this can escalate into cirrhosis. Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus dramatically increases the incidence of liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma). Alcohol increases the risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer for chronic carriers.

About one to ten percent of HBV-infected people experience symptoms outside of the liver, including serum-sickness-like syndrome, membranous grlomerulonephritis, acute necrotizing vasculitis, or popular acrodermitis of childhood, also known as Gianotti-Crosti syndrome.

The serum-sickness-like syndrome often precedes the onset of jaundice, as it occurs in the early development of Hepatitis B. Clinical characteristics include skin rash, fever and polyarteritis. The symptoms usually subside after the onset of jaundice, but not in all cases. Symptoms may persist throughout the entire duration of acute Hepatitis B.

Roughly 30 – 50 percent of all people with acute necrotizing vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa) carry the HBV. HBV-associated nephropathy is more common in children, but can affect adults as well.

Manifestation

The Hepatitis B virus interferes with the functions of the liver first of all by replicating in liver cells (hepatocytes). NTCP is a functional receptor, and evidence suggests that carboxypeptidase is the receptor in the closely-related duck hepatitis B virus.

When HBV infection occurs, the host immune response causes not only hepatocellular damage, but also viral clearance. The innate immune response may not play a major role in these processes, but the adaptive immune response – particularly virus-specific cytocoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) – plays a part in most of the liver injury associated with HBV infection. CTLs kill infected cells and produce antiviral cytokines to eliminate HBV.

These cytokines are then used to purge HBV from viable liver cells. CTLs initiate and mediate liver damage, but antigen-nonspecific inflammatory cells can worsen CTL-induced immunopathology. Platelets activated at the side of infection, meanwhile, may facilitate the CTLs accumulation in the liver.

Hepatitis B Transmission

Transmission of the Hepatitis B virus can be achieved through exposure to infectious blood or bodily fluids such as semen and vaginal fluids. Potential means of transmission include sexual contact, blood transfusions, transfusion with other human blood products, re-use of contaminated syringes and needles, or vertical transmission from mother to child during childbirth.

Without intervention, a woman who tests positive for HBsAg virus carrier a 20 percent risk of passing the infection to the baby during childbirth. If the mother is also positive for HBeAg, the risk of passing the infection to the offspring during childbirth goes up to a whopping 90 percent.

The Hepatitis B virus can also be transmitted between people living in the same household through contact of nonintact (damaged) skin or mucous membrane with secretions or saliva containing HBV. On the other hand, at least 30 percent of all reported Hepatitis B cases among adults do not have an identifiable risk factor. Research also showed that breastfeeding did not contribute to the transmission of the infection from mother to child during childbirth, provided that the mother had proper immunoprophylaxis.

Detection and Diagnosis of Hepatitis B

The tests for detecting Hepatitis B virus infection are called assays, and involve serum or blood tests. They are designed to detect either viral antigens, i.e. proteins produced by the virus, or antibodies produced by the host.

The most commonly used method to screen for the presence of Hepatitis B infection is the Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) mentioned earlier. Early in the infection, however, this antigen may not be present. In such cases, it may also go undetected later in the infection, as the host clears it. Most Hepatitis B diagnostic panels contain HBsAg and total anti-HBc for a more accurate diagnosis.

Shortly after the HBsAg appears, another antigen called Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) appears as well. The presence of HBeAg in a host’s serum typically involves higher rates of viral replication, as well as enhanced infectivity. On the other hand, variations of the Hepatitis B virus do not produce the “e” antigen, which means this rule may not always apply. The HBeAg may be cleared by the host during the natural course of an infection, and antibodies to the “e” antigen (anti-HBe) will kick in immediately afterwards. This conversion has often been tied to a dramatic decline in viral replication.

If the host can clear the infection, the HBsAg eventually becomes undetectable and is followed by lgG antibodies to the hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs and anti HBc IgG). The period between the clearance of the HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs is called a window period. If an individual tests negative for HBsAg but positive for anti-HBs, it means that either the infection has been cleared, or the patient has been vaccinated. Patients who remain HBsAg positive for more than six months are considered Hepatitis B carriers.

Hepatitis B virus carriers may have chronic Hepatitis B. In this case, they would exhibit elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and liver inflammation, as revealed by biopsy. Meanwhile, carriers who reached the HBeAg negative status, especially individuals who contracted the infection as adults, have very little viral multiplication, therefore have little risk of long-term complications or of further transmitting the disease.

Hepatitis B Prevention

As previously mentioned, Hepatitis B virus infection can be prevented through vaccination, and there are several vaccines available. These vaccines rely on the use of one of the viral envelope proteins (HBsAg). While the vaccine was originally prepared from plasma obtained from people with long-standing Hepatitis B virus infection, it now involves a synthetic recombinant DNA technology that does not contain blood products. There is no risk of infection with Hepatitis B from the vaccine.

Administering the Hepatitis B vaccine (HBV 1) and Hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) to an infant within the first 12 hours of birth can lower the risk of transmission from mother to newborn from 20 – 90 percent to just 5 – 10 percent. This initial vaccine must be followed by a second dose of HBV 2 at 1 – 2 months and a third dose after six months (24 weeks).

Roughly two percent of infants who receive the vaccine will not develop immunity after this series of three vaccines, so infants born to Hepatitis B-positive mothers are tested again at nine months for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and the antibody to the Hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs). If test results reveal that the child is still susceptible even post-vaccination, a second series of three doses (0, 1 and 6 months) is administered. In some cases, the child remains susceptible even after the second series, but a third series is not recommended.

The vaccine is administered in either two-, three- or four-dose schedules in infants and adults, providing protection for up to 90 percent of people. Individuals who show adequate initial response to the primary course of vaccinations may be protected for as long as 12 years, and the immunity is estimated to last at least 25 years.

As Hepatitis B is transmitted through bodily fluids, adequate prevention includes avoiding unprotected sexual contact, blood transfusions that are not properly tested, re-use of contaminated needles and syringes.

Hepatitis B Treatment

Because most adults clear the infection spontaneously, the Hepatitis B infection does not typically require treatment. Less than one percent of people may need early antiviral treatment if the infection takes a severely aggressive course such as fulminant hepatitis, or if the patient’s immunity is compromised.

Treatment of chronic infection, however, may be required to reduce the risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer. Patients with chronic infection and persistently elevated serum alanine aminotransferase and HBV DNA levels should get treatment. The therapy may last between six months and a year, depending on the medication and genotype.

None of the currently available drugs can clear the infection altogether, but they can prevent the virus from replicating and keeping liver damage to a minimum. The U.S. has seven medications licensed for Hepatitis B treatment infection as of 2008.

These medications include antiviral drugs lamivudine (Epivir), adefovir (Hepsera), tenofovir (Viread), entecavir (Baraclude) and telbivudine (Tyzeca), as well as two immune system modulators – interferon alpha-2a and PEGylated interferon alpha-2a (Pegasys).