Theories likely to explain supernatural phenomena are unfortunately not encountered every day. This process is often long, complex and full of obstacles. In addition, as French philosopher Bernard de Fontenelle remarked, before looking for an explanation of a phenomenon, we must be sure that it really existed. This remark may seem comical, but in this area, on the border of reality, it is sometimes difficult to do. It is easy for a court to establish a person’s guilt when there is material evidence. But it often happens that there is neither one nor the other… and in this case, what should the court do?

Witch burned at the stake in the Middle Ages

Diving in the water and guilt

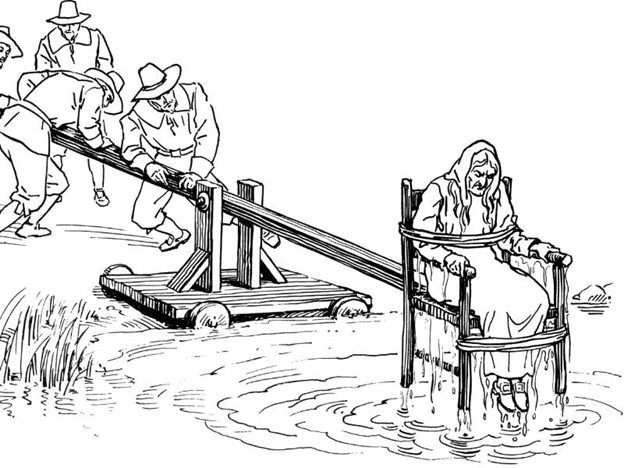

Following a crime, two procedures were once used to determine the guilt of an accused: one was to weigh them, the other was to immerse them in cold water. It should be noted that the latter method was first mentioned in the 14th century BC.

Any accusation concerning the fidelity of a married woman necessarily involved the “Judgment of God”; the unfortunate was submerged in water, which had to swallow or repel her, as it was innocent or guilty. A similar attempt is described in Avesta, a collection of Iranian sacred texts (IX-VII BC). It is also mentioned in Manu’s Laws (Manava-dharma-sastra,), a code of Indian law dating from the second century BC.

Witch submerged in water

Finally, this form of “legal evidence” was applied in medieval Russia to those accused of witchcraft. Priest Serapion of Vladimir (13th century) speaks of this in the following terms: “Throw her into the water and look; if she drowns, she is innocent, but if she manages to swim she is definitely a witch”.

Tens of thousands of wizards burned at the stake during the Inquisition

In Western Europe, people suspected of having made a pact with the devil were subjected to “water trials” or scales (Tens of thousands of witches and wizards were burned in the Middle Ages at the stake of the Inquisition).

However, the paradoxical nature of the results, often challenged in the case of these judicial inquiries, prompts us to ask questions about their reality.

If you floated, you would then die burned at the stake

The “water test” was practiced in public. The person to be subjected to the “judgment of God” was undressed and bound in such a way that the thumb of the right hand was attached to the thumb of the left foot and vice versa. Then the person was immersed in running water along a rope. Those who floated ended their days at the stake.

Witch immersed in running water

According to some witnesses, the accused remained in the water for half an hour, floating like a cork or a piece of “shoe wood” (in Europe, poplar, willow, etc. were used to make shoes.)

The “scale test” or the fat ones are innocent

The test consisted of weighing the defendant. His innocence was only proven when his weight exceeded a certain limit. If not, he was sentenced to a “mild, bloodless punishment,” as the torture of fire was hypocritically called in the Middle Ages. The critical weight varies by city. At the Oudewater, for example, it was 49.5 kg; at Munster, 55 kg, in other cities from 11 to 14 pounds (4.5 to 5.6 kg – the weight of a baby!) A question arises: what was the minimum weight recorded during the trial?

A newspaper that appeared in Austria-Hungary at the beginning of the 18th century relates a curious episode: “When several people were arrested on charges of witchcraft, they were weighed, as usual… It was found that a busty woman weighed 1.5 loth and her husband who was not skinny either, 1.25 loth ”

Given that the Austrian loth has a value of 17.5 grams, it results that the man and the woman each weighed 20-30 g. In such a case, one can cite an old axiom of law: res facit cui prodest (the work was done by the one who takes advantage). Who could take advantage of counterfeiting? By no means the defendant, who didn’t want to climb on the scaffold at all. But neither the inquisitors, who would not have resorted to these attempts if they had to falsify the results.

Balances for wizards

The first scale is believed to have been manufactured over 6,000 years ago. Its representation is on a pyramid in Giza. The theory of scales was studied by Aristotle, Euclid and Archimedes. The scales built by the Arabs in the Middle Ages allowed the weighing of objects with an accuracy of 0.005 g. The best balance is the one with ropes. A scale of this type (used by the Inquisition, at the request of Charles V, to weigh witches or magicians) is currently exposed at Oudewater City Hall in the Netherlands. It is exactly the same model that has been in other cities in Western Europe.